Walking

through dew-lit grass in the early hours of late summer mornings conjures a

specific memory for me, and I’m surprised what a hold it still has on my

senses. It’s a mix of nerves, dread, and nausea. I played soccer for my

formative years, from the ages of five to sixteen, and in the later years of competitive

play, training began in August (though unofficially all year). I was never a

good or happy runner. There was this one particular run in pre-season training

where the last mile was uphill (and was aptly named “suicide hill”). It was

through a thickly forested area, which provided some refreshing shade from the

August sun. Even so, this part of the run was the worst, the most difficult,

the most tiring, the most painful—and it was also when I had no clear idea of

where I was in my run—I knew I was towards the end, but how close? And that

thought—how much farther?—nearly drove

me mad. Other girls were passing me, seemingly energized by the thought that

they were almost done, while I felt more discouraged than ever. Their breathless,

motivational exclamations as they passed did the opposite of motivate—I wanted to

be maliciously clever, but I mercifully didn’t have the energy even to spit.

Then

I’d crown the hill, and just like that I was in suburbia, the dark forest

behind me, running down the paved road towards the soccer field where most of

my team waited (yes, I was usually last), bent over, guzzling water, or lying

on the ground in a sweaty mess.

I

can honestly say that, while I don’t willingly subject myself to running as an

adult, I am grateful for that experience—for the discipline, the drive, and

just to know that I could do it and not die. But that moment on “suicide hill”,

those aching minutes where I was haunted with the thought of how much farther has come to my mind repeatedly

in so many other instances—in labor, in difficult relationships, exhausting

days, Job-like years of life—and even annually in Lent. How much farther?

This Lent hasn’t been particularly trying for me, in fact it’s been sprinkled with graces. But the past week has been like trudging through mud. The daily grind of life was grinding me down and I really wanted to hit up my old stand-bys for comfort and sustenance, the very things that I’d given up for Lent (or that I’d given up for life). I’d failed, tripped up under the cross, and felt like an embarrassed child at the foot of Our Lord, half hiding my face, half ignoring Him. To indulge the metaphor, I was stuck on “suicide hill”, only thinking about how hard it was, how much I hurt, and not looking up and ahead towards the finish line.

Yesterday,

my family and I trekked an hour and a half north to visit a

monastic-community-in-formation. The Maronite monks of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph

are in the process of building a monastery in Castle Rock, Washington. Their

enthusiasm and love for the faith, vocation, Our Lord and thus His people, is

infectious and inspiring. Even though I was dreading the drive through a

mud-puddled highway and spatially-challenged vehicle, it was well worth every

minute of car bickering and the penitential porta-potty.

Aside from the beautiful divine liturgy (which was food for my soul!), the homily, augmented after Mass in Abouna’s announcements, was all about answering, “How much farther?” In short, we’re at Passiontide, only two weeks away from Easter. But the real answer is eucharistia, a word that’s chock-full of meaning. In Greek, it means thanksgiving; for Catholics our Eucharistic feast is an offering of thanksgiving as we receive our Lord’s Body and Blood. As I listened to both priests, I thought of quotes I have on my frig (that I apparently need to be looking at more often) that read, “Gratitude is the root of joy,” and, “Gratitude is the beginning of trust.” As I took the Body of Christ that had been dipped in the Precious Blood, I was reminded to not only make an act of thanksgiving for this Eucharist, but that this was the true sustenance that would help me get through to the end.

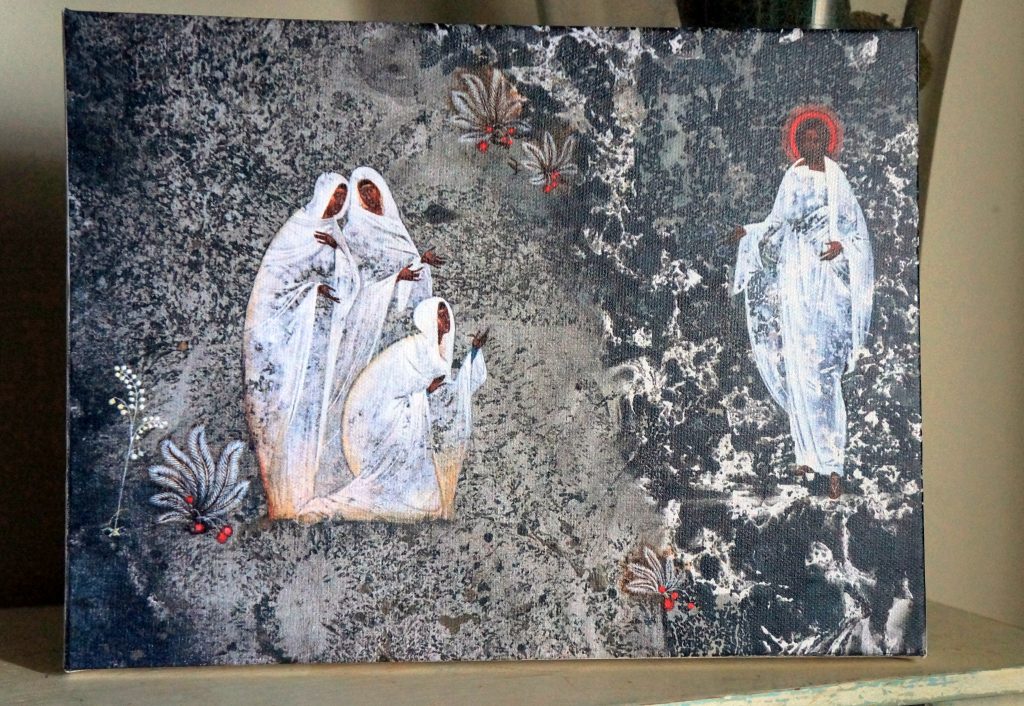

Another message of these holy priests that was echoed in today’s readings and a rich homily from our own parish priest, was that as we continue on to the end, not to look back. “Go and sin no more,” Jesus said to the woman caught in adultery. It reminds me of how often Jesus said to paralytics, “Pick up your mat and walk,” as though to say, your half-lived existence is over—go and live fully, sin no more, take your light into the darkness, baptize nations, preach the good news, etc. Lent is the time to renew repentance, and renew the Christian life. Only with eucharistia—with gratitude and the Eucharist—can I accept what has been and have the strength to move on.

Thinking

back to “suicide hill” and that run of all runs, I got lost in what I had run

to that point. I was overcome by how far I had run, and was sure I couldn’t

finish the race. My teammates who passed me were thinking about the finish

line, not about the space between.

The answer is not to look behind where lie our failures or even past glory, but to look up and ahead where Christ is raised up on the cross. I have been thinking a lot about two “secular” songs this Lent—“Hurt” by Nine Inch Nails (Johnny Cash’s cover) and “I Can Change” by Lake Street Dive. These songs echo the self-loathing that either precedes repentance and new life, or despair and death. In any perpetuating sin or addiction, it is our past failures that take our eyes off of what’s ahead and concentrate instead on sin. It’s not a lack of knowledge of our shortcoming, but a deafening awareness of it that drowns out hope and chokes our joy. It takes strength and humility to call out to God who is all too eager to wipe out our offenses and give us new life. But if we allow Him to do that, we need to think on it no longer, to keep no record of our failings once they’re offered up in the sacrament of reconciliation, but to be content to “go, and sin no more”, over and over again, until the final race is run.

I for my part do not consider myself to have taken possession. Just one thing: forgetting what lies behind but straining forward to what lies ahead, I continue my pursuit toward the goal, the prize of God’s upward calling, in Christ Jesus.

Philippians 3:13-14