It’s Holy Week, the last week of Lent— and the third week of Oregon’s social distancing mandate because of the coronavirus pandemic— and the third week without Mass. It’s so strange to think of not going to Mass during Holy Week. I was doing okay with it. I was like, yes Lord, tell me what you want me to learn from this Eucharistic fast. And, as usual, my stamina began to give way. Fortitude is not my forte. I went to Confession (thank God we still have that) and afterwards found myself weeping like a Magdalene at the doors of the Church (“Where have you put my Lord?”), knowing Father was saying Mass just twenty yards away—our Lord was so close, but I couldn’t touch Him or see Him, let alone partake of His Body and Blood. My eldest daughter, who was with me at the time, looked perplexed as I sobbed all the way home.

I texted a friend later and she had some very wise words that gave me peace and strength. She said my tears were a gift from our Blessed Mother on the eve of Palm Sunday, a gift to know a part of her sorrows as we begin Holy Week. Her beautiful words reminded me of something I had recently been pondering.

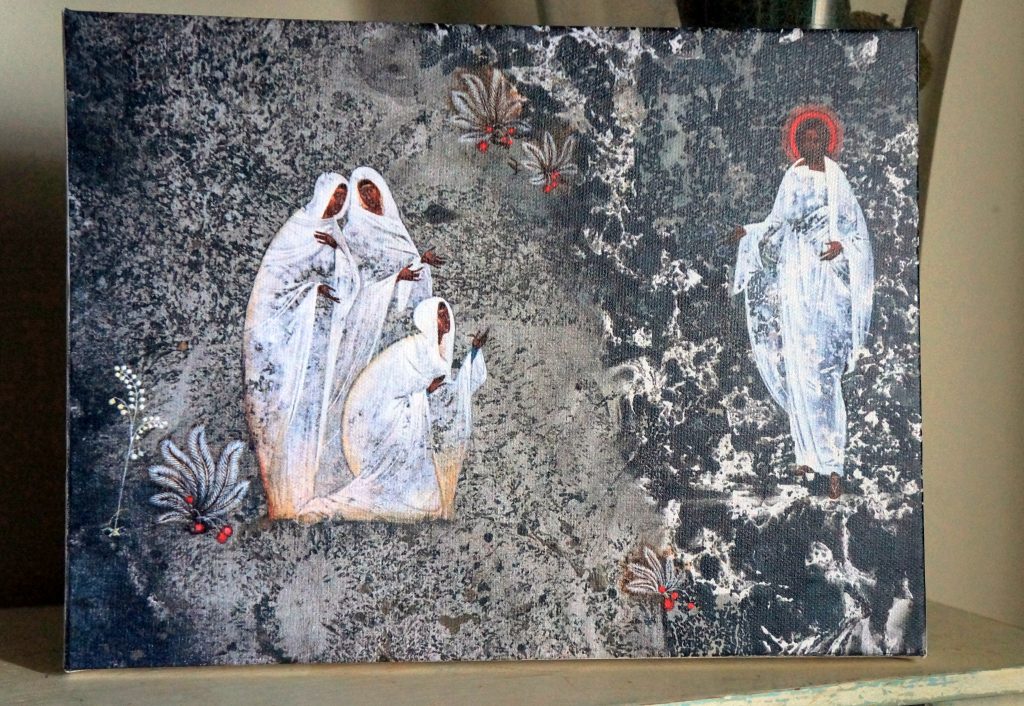

Just a week into the Oregon quarantine, my birthday present from my husband arrived one month late from the Ukraine. The timing couldn’t have been more providential. It was an icon of the resurrected Lord in the garden with three women looking on from a short distance away. It’s an icon I’ve been wanting for a while; about a year ago, while praying through the Consecration to Jesus through Mary, I was moved by the story of Mary Magdalene in the Gospel of John when, while weeping at the empty tomb, she recognizes Jesus’ voice calling her by name. Though I’ve heard and read that story many times, it struck me deeply as I imagined myself at the empty tomb, as I imagined Jesus calling me by name. Ever since then, my devotion to Mary Magdalene has grown as I’ve realized more ways I feel connected to her. This icon was the closest I could come to that beloved story in the Gospel.

But the icon offered so much more than what I had initially seen in it. As soon as I unwrapped it, my 13-year-old artist-daughter noted how fitting an icon it was for this strange time we’re in without Mass: we, like the women in the garden, gaze at our risen Lord, but are unable to get much nearer.

Prompted by her introspection, I meditated on the icon for a time, alone. I realized the three women were in the same shape that, in other icons, Christ’s hand takes as he makes the sign of the Trinity. The two standing women are turning towards one another with their hands gesturing towards the risen Christ. But the third woman, who I assume is Mary Magdalene by her posture, is kneeling and reaching towards Jesus. Everyone is dressed in white with accents of red, symbols of purity and the Spirit. Their white clothing is almost transparent, signifying the temporality of this world, but their faces and hands are solid, signifying the immortality of the soul. The icon is split unevenly down the middle: the side that Christ stands on has more depth, and seems to be higher ground, while the side the women are on is less defined and more flat. Christ’s hand reaches out towards them, palm-up. He is not going towards them, but greets and beckons generously; he does not look as though he’s there to dry their eyes, but stands matter-of-factly, as though His risen body is His testament, the proof of His love for them.

I’m not sure where I’m going to hang this icon; for now it is beside my bed so it is the first and last image I see in the day (besides my husband’s handsome face, of course). It has been a true gift for my heart during this time away from Our Lord’s table, and a reminder not to squander it (which I’ve definitely done at times). Ideally, love and desire should increase, a gratitude for the unique mystery of the Eucharist should strengthen, and awareness of my brothers and sisters throughout the world who live without the Sacraments readily available should take root in my heart where an on-going prayer for them can manifest.

What will Easter be like without a Eucharistic feast? I don’t know; probably sad to a degree, maybe anti-climactic. It’s good to feel that loss, to hate going without. But it will be a good spiritual exercise to remember our Blessed Mother and the women at the tomb who, though they could not touch Him as they could before, were overjoyed that He was truly risen.