{aaaahhhhhhhh!!!}

In January of last year—2021—my lady-friends at church and I got together for a friend’s birthday. The birthday girl requested we come to the gathering with “a word”. A word-of-the-year: apparently, it’s a thing. I immediately went to sarcasm and thought of every children’s television show with their words of the day: would Word Girl greet me mentally every morning, her cape flowing behind her, with a reminder of my word-of-the-year? It was hard not to imagine Pee-Wee Herman screaming in hysterics with giant underwear on his head every time this word-of-the-year would be uttered. That’s where my brain goes, what can I say.

aaahhhhhhhh!!!

But the pop-up image of Pee-Wee Herman wearing giant underwear on his head wasn’t the only turn-off to this exercise. I admittedly have a knee-jerk repulsion to female groupings of any kinds—prayer groups, Bible studies, book clubs—which is objectively unjust and something I’m in the process of examining and hopefully rectifying. That being said, my first reaction to my friend’s request was panic and repulsion. But I simmered-the-hell-down and realized the more appropriate and reasonable response between avoiding the get-together and making up a saccharine and dishonest response, was to politely decline word-choosing and be a good listener.

This lady-friend group continually challenges my repulsion towards lady-groups with their sincerity and generosity of spirit. And this was no exception: as I sat and listened to their honest, and non-saccharine responses, my heart softened. I understood more the purpose of the exercise, and in that moment of emotional receptivity, a word floated into my head: healing.

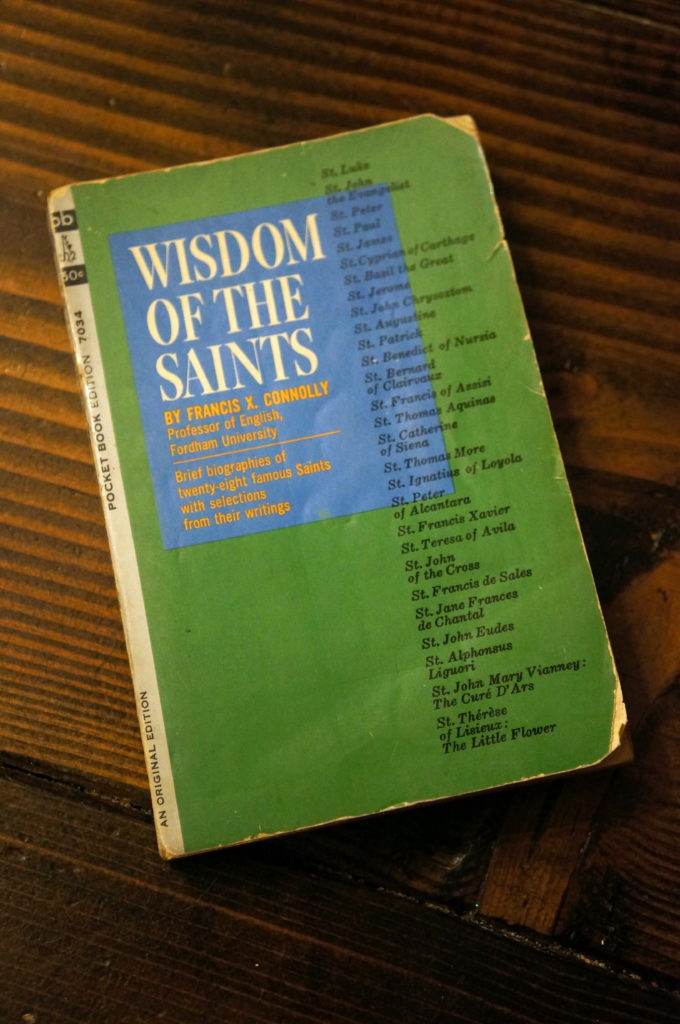

I was pregnant, due that May, and I had approached and begun this pregnancy with the intention of learning to trust God more fully. There were a lot of knowns and unknowns to fear with this pregnancy. I had been praying for complete and total healing, but also that God would help me trust Him more, whatever the outcome. St. Gianna Molla’s mantra of whatever God wants was purposely on my lips, even though there was fear in my heart.

I swallowed my pride and suspicion and told my friend later that week what my word-of-the-year was. She was a physician, a mother of four, and a recent convert to Catholicism. She explained that she wanted to know her friends’ words so she would know how to pray for each of us. And later that year, she would—unbeknownst to me—begin a novena to St. Gianna Molla towards the end of my pregnancy when things got scary. It would be Gianna’s feast day when I was finally released from the hospital. Only then did my friend let me know about her novena, and it had been the first time she had ever entrusted a prayer to the intercession of a saint.

It is experiences like these when I feel God lighting a loving flame to melt one more hardened, sarcastic piece of my soul. My friend requested vulnerability, which I systemically responded to with suspicion. But through the vulnerability of my friends, my own heart was softened so that I could hear the Holy Spirit whisper, “Healing.” That year—2021—really was a year of healing, but in more ways than I could have anticipated. God needed to prepare me, needed me to have my eyes wide open and my heart attentive. Even though the prayer for healing was already on my lips, I needed to entrust that to the body of Christ, these lady-friends with open hearts.