There’s an old

home video I like to watch from when I was around two years old. My dad had

just bought a video camera—a technical monstrosity with a blinding lamp—and was

Memorex-ing the whole of Christmas. In the video, my aunts and uncles are

sitting on orange velour couches, while the litter of cousins enter and exit

randomly. One of my uncles is doing a Dolly Parton impression with balloons

stuffed up his shirt, after which my dad’s other siblings try to top it with

their own joke or impression. They’re all making fun of each other, vying for

attention, laughing. Like all families, this is certainly part of the story,

but not all of it. No one records the ugly stuff—who wants to relive that?

By the time I was

an adolescent, I was aware that a lot of my family were drug-users. But it wasn’t

really called “addiction”, it was more like uncle-so-and-so just can’t get his

act together. My siblings and I thought our family was pretty amusing,

actually. They had become caricatures to us: the uncles who couldn’t keep still,

their cigarettes bobbing like teeter-totters between their fingers, dropping

ashes on the carpet; the cousin who lives as a purposeful transient with his

dog, waxing philosophical, and sharing the augmentation of his thoughts by psychedelic

shrooms; the aunt who moves like honey and touches her nose to mine to tell me

all about my zodiac that month. It all sounds like great material for a novel,

these portraits of pitiable, but amusing characters. We loved them, and laughed

at them.

One uncle in particular was the most advanced as a caricature in my mind; he was also the most far-gone. Years of heroin, followed by years of state-funded methadone, had reduced him to a shadow of a person. He babbled nonsense and had black gaps in his mouth from decay. We saw him less frequently as time went on. I remember the last time I saw him; I remember his profile as he chatted with my great-aunt, who, though thirty or so years his senior, looked the same age.

The next time I thought

about him was when we found out he had collapsed and been taken to the

hospital. Dirty heroin had caused an infection in his body, and after decades

of abuse, his organs began to fail. At the age of 44, his body shut down,

swelled up, and was nearly unrecognizable before he died. My grandmother, who

was in denial about the rampant drug-use throughout the family, did not want

drugs to be at all mentioned in the cause for death. But we all knew drugs had

killed him, slowly over decades.

It all happened in

one night—the call, the hospital, his death—then I went to school the next day.

There was no mourning. When someone like that dies slowly over time, you grieve

them in pieces. When you first realize they’re using and don’t want help, you

grieve. When they choose drugs over their spouse and children, you grieve. When

you realize they can’t keep a job and won’t be able to take care of themselves,

you grieve. Every time you see them slip into greater despair, you grieve. Simultaneously,

you learn how to let go, or you go mad.

His memorial

service was a strange event; I don’t remember drugs being mentioned at all.

There was a brief obituary, then we all sat in silence while Norman Greenbaum’s

rock classic “Spirit in the Sky” played over the speakers. In the foyer,

someone had put together a photo collage with pictures I had never seen before

of an uncle I didn’t recognize. He was striking with dark hair, strumming a

guitar. That day I learned he had been a musician, an actor, and an athlete. This

caricature of a person became more real to me at his passing. He became a man

with a past, someone who had once lived a real life with aspirations and love. I

wondered how he could have become a shell of that man.

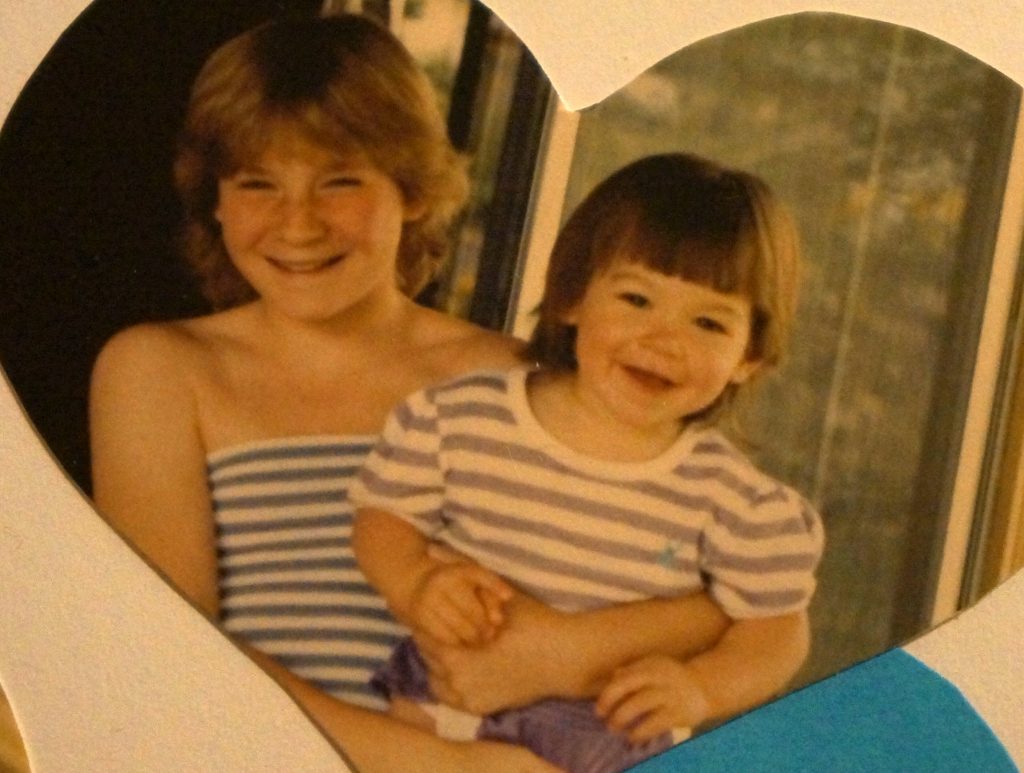

Like many

families, the cycle of addiction continued with mine into the next generation. One

who has been tragically affected is my sister. Another reason I like to watch

and re-watch the home-video I mentioned earlier is because my sister, always

one who loved attention, is in a lot of it. That is the sister I remember:

spunky, fun, giggly, sassy, energetic; she was my playmate, even though she was

ten years my senior. Like our uncle who passed away, she is now a shell of that

person. I do not recognize her.

The tragedy is

that drugs do make people into caricatures of the drug they use. The old adage “you

are what you eat” works quite well with addiction; in this case, the user

becomes the substance. Meth users, heroin users, coke users, abusers of

prescription meds—each has a personality of sorts as the real person slowly slips

away. No one uses drugs to purposely mess up their lives, rather they use to dull

a pain or to drown out lies of inadequacy. Sadly, the drug or alcohol just

confirms the fear of not being enough, of not having what it takes, of being

unloved. Spiritual and physical sustenance becomes secondary; shit becomes

primary. Everyone who really loves them becomes an enemy outsider. The devil

must just love it.

I didn’t know my

uncle when he was a handsome, talented young man. I don’t remember his years as

a husband or a father. I didn’t have to mourn the loss of him in that way,

though as a teenager I was very struck by his sudden and tragic death. But I am

in the process of grieving the loss of my sister. I don’t know if we’ll ever

get her back. Out of my own despair and anger, I have been tempted to

caricaturize her, to make light of her, to scorn all her selfish choices. But

that’s the work of the drug, to dehumanize her, and I can’t give in to that.

In my better

moments, I cling to Scripture passages about hope, about leaning not on our own

understanding, but on the delicate and powerful workings of the Holy Spirit. My

hope and prayer is that she will one day hear God calling her by name, out of

despair and darkness. I want Jesus to break through to her, to appear before

her like He did to St. Paul, blind her with His light and heal her with His

love. But as far as I know, He could be trying this every day. After years of dealing

with addiction in my family, then learning through Al-Anon and its affiliated

literature, I know it’s not simple. God doesn’t force grace upon us; we must

cooperate, ask and receive. I know He loves her more than me, more than my

blesséd parents who hope, pray, and wait, who search for her like a lost sheep.

And perhaps God did do this with my uncle, in those last hours so close to

death; as the world watched him in a sleeping silence, perhaps God was bursting

through with a healing balm of love and mercy, and he was finally desperate

enough to whisper his fiat, his yes

to God. I guess that’s why we pray continually, for the mercy of just such a

moment.